The CIDA Worker Who Leaked Canada’s Support for Pinochet

One act of defiance can change history.

On September 11, 1973, Chile’s democracy was violently overturned. General Augusto Pinochet, with support from the CIA, launched a military coup against President Salvador Allende, the democratically elected socialist leader. What followed was a reign of terror: students, intellectuals, union leaders, artists, and journalists were tortured, executed, or simply disappeared. Even so, a little over two weeks after the coup, Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal government officially recognized Pinochet’s regime.

In the chaotic aftermath of the coup, thousands of Chileans sought to flee. Some desperate individuals arrived at Canada’s embassy in Santiago, hoping for sanctuary. A few were allowed in by Marc Dolgin and David Adam, young diplomats in charge of the embassy while the ambassador was travelling. However, Canada had no formal refugee policy. Worse still, those escaping Pinochet’s repression were often viewed with suspicion in Ottawa due to their leftist affiliations—a concern partly framed by Cold War thinking. The Trudeau government—already aligned with Washington’s hostility toward Allende—was reluctant to open Canada’s doors to those it perceived as socialist dissidents.

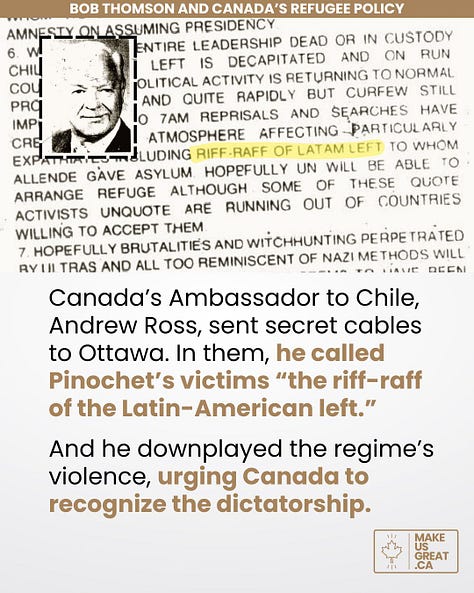

Canada’s ambassador to Chile, Andrew Ross, played a key role in shaping this policy. In a series of confidential cables sent to Ottawa in the days following the coup, he dismissed those being persecuted as “the riff-raff of the Latin American left.” He minimized the military’s abuses, describing killings as “abhorrent but understandable” and said he saw no reason for Canada to delay recognizing the new dictatorship.

Economic interests also loomed large. Despite resisting close relations with Allende, Canada had a growing trade relationship with Chile, and shortly before the coup, de Havilland Aircraft of Canada had signed a $5 million agreement to sell six Twin Otter aircraft to Chile’s domestic airline. However, as loan guarantees to support the sale had not yet been finalized with the Export Development Corporation, de Havilland officials quickly lobbied the Department of External Affairs. They feared the sale would fall through unless Canada recognized the new regime.

The Globe and Mail reported at the time that Pierre Charpentier, head of the Latin America division at External Affairs, admitted that “trade considerations were the foremost factor” in Canada’s swift recognition of Pinochet. Though the department later denied the aircraft sale specifically was a major factor, it did not counter the broader assertion that trade and business concerns played a key role in its decision. Prior to Allende’s ascension, in fact, Canadian mining company Noranda partly owned the Chuquicamata copper mine, but the leftist government nationalized the operation. It was only during the Pinochet years that Noranda regained ownership of its Chilean subsidiary.

Canadians were critical of their government’s decision. Media outlets such as the Montreal Gazette and Toronto Star condemned the recognition, while, as UBC political scientist James Rochlin noted, “a plethora of interest groups, especially church organizations, staunchly criticized” the Trudeau government. Dissent also emerged within the federal public service.

Bob Thomson, a young worker at the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) in Ottawa, was outraged by Ross’ characterizations and the government’s complicity. Determined to expose the truth, Thomson secretly leaked Ross’ cables to the New Democratic Party (NDP). The revelations ignited a political storm and increased public pressure on the government.

Initially, External Affairs Minister Mitchell Sharp reiterated the ambassador’s downplaying of the violence in Chile. However, growing outcry forced him to send Geoffrey Pearson, a senior official, to Santiago to assess the situation firsthand in November. Pearson returned a week later with troubling findings—confirming the extent of the repression and the legitimate fears of Chileans seeking refuge abroad.

Within weeks of Thomson’s leak, the first group of Chilean refugees arrived in Canada. Eventually, 7,000 Chileans found safety under Canada’s special Chile program. The leaks played a crucial role in forcing a shift in policy, and the public response helped drive long-term reform. This episode of reckoning directly influenced the creation of the Immigration Act of 1976, which formally established refugee status as an immigration category, bringing Canada in line with the UN Refugee Convention.

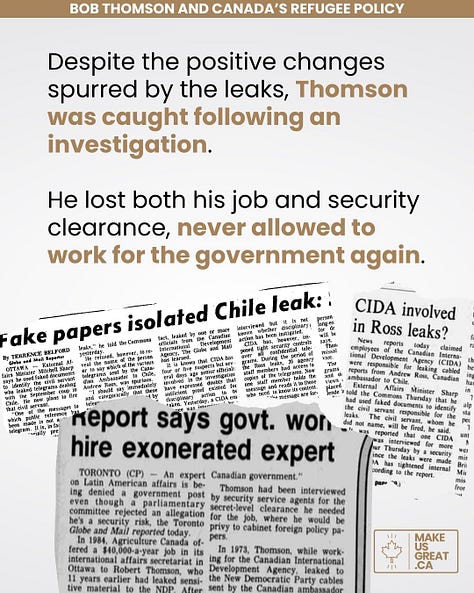

Despite his impact, Thomson paid a steep personal price. Following an internal investigation, he was caught, dismissed from his position, and had his security clearance revoked—forever barred from government work. Yet, he never stopped fighting for justice. He went on to work with Oxfam Canada, played a leading role in the early days of Bridgehead, the fair trade coffee company, and was instrumental in introducing Fairtrade labeling to Canada.

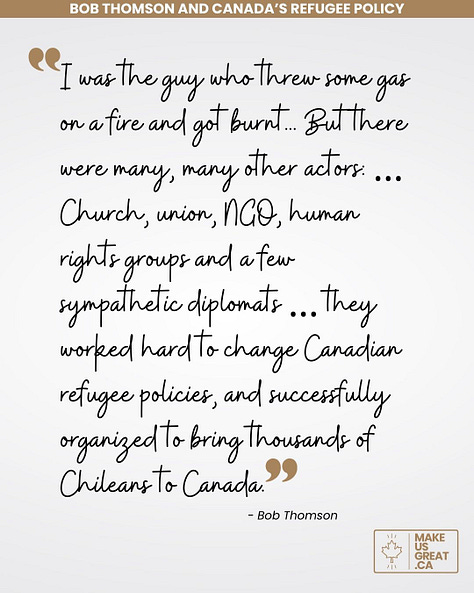

Reflecting on his role years later, Thomson remained humble. “I was the guy who threw some gas on a fire and got burnt, losing my job at CIDA in the process,” he said. “But there were many, many other actors: churches, unions, NGOs, human rights groups, and a few sympathetic diplomats… they worked hard to change Canadian refugee policies and successfully organized to bring thousands of Chileans to Canada.”

Thomson’s story is a testament to the power of moral courage. His actions helped shape Canada’s refugee policies and provided thousands of Chileans with a second chance at life. Though he sacrificed his career, his legacy endures in every life he helped to save—and in a Canada that, despite its flaws, became more open to those fleeing persecution.