The Fund That Could Have Been

Alberta’s great savings failure.

As Alberta’s separatist sentiment simmers, a question looms: what would an Alberta standing on its own actually look like, financially? Separatists envision a self-reliant province flush with oil and gas wealth, capable of shouldering the costs of statehood—from embassies to armed forces. But this vision hinges on a critical assumption: that Alberta would manage its finances and resource wealth wisely.

Unfortunately, history suggests otherwise. The province’s mismanagement of its oil and gas revenues—best illustrated by the dismal state of the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund—exposes a deeper problem. The decades-long failure to convert Alberta’s natural riches into lasting financial security is a cautionary tale.

The Heritage Fund was created in 1976 by Peter Lougheed’s Progressive Conservative government to ensure that non-renewable resource revenue would be used to invest in projects aimed at improving the lives of Albertans, strengthen and diversify the economy, and save money for a future where oil and gas reserves become depleted.

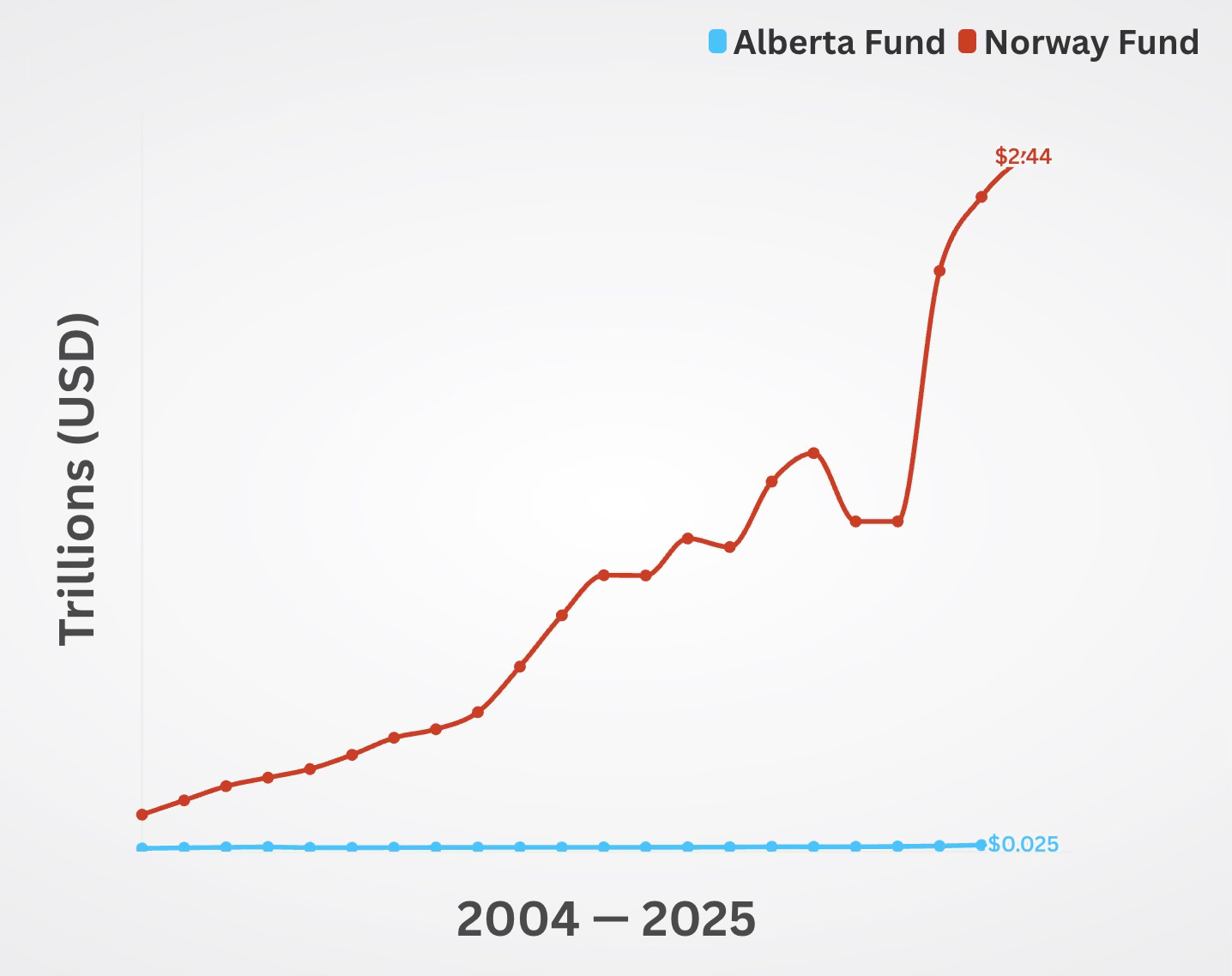

Almost 50 years later, the Fund’s value sits at $25 billion. While that figure might seem large at first, it pales in comparison to the current value of resource wealth funds set up by other jurisdictions. The most striking comparison is with Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), created in 1990.

Norway’s two trillion dollar nest egg

Despite starting 14 years after Alberta’s Fund, Norway’s Fund ended 2024 with a staggering value of over $2.4 trillion (CAD)—nearly 100 times Alberta’s Fund. Norway and Alberta have similar populations—5.6 million versus 5 million—meaning the GPFG saves close to 90 times more per person than the Heritage Fund.

Of course, no comparison is perfect. For one, Alberta’s heavy bitumen blend fetches a lower price on markets than Norway’s higher quality, light, sweet crude oil. And, unlike Norway, Alberta has no direct access to tidewater, meaning shipping oil is relatively more expensive. These two factors combined mean that although Alberta produces more barrels of oil than Norway, Norway’s oil production is valued higher in dollar terms.

This explains some of the difference in the size of the two funds, but there’s far more to the story. Though provincial governments at first contributed annually to the Heritage Fund—30% of oil and gas revenues until 1983 and then 15% until 1987— subsequent governments stopped doing so. Between 1987 and 2005, a lengthy period spanning the successive conservative governments of Don Getty and Ralph Klein, the province made zero transfers. Since then, contributions have been minimal and sporadic. And governments regularly raided interest income to pay for general government expenses. Consequently, from the time the Heritage Fund’s per capita value peaked in 1983, it has declined in real terms by more than half.

In short, Alberta’s governments since the mid-1980s have so thoroughly lacked a culture of savings and responsible resource wealth management that, whether in boom times or bust, the Heritage Fund was left to wither away.

Alaska’s oil dividends

While the Norway example is striking, a comparison closer to home offers another stark contrast. Alaska created its Permanent Fund in 1976, the same year as Alberta, to save the state’s oil wealth for future generations. Today, it’s valued at $113 billion (CAD), over four times the Heritage Fund. Given Alaska’s small population of about 740,000, however, the Permanent Fund saves thirty times more per person than Alberta’s fund.

Uniquely, Alaska’s Fund pays an annual dividend to every resident, including children. This has been characterized as the only long term universal basic income program in the world. In 2024, the dividend was set at $1,702 (USD), meaning that a family of four received a $9,531 (CAD) direct cash transfer.

It goes without saying that Albertans receive no such annual payout. The closest they’ve come is the Prosperity Bonus, more commonly known as Ralph bucks—a one-time payment of $400 from the government back in 2006, when the provincial coffer was overflowing with resource revenues driven by high oil prices.

Critically, Alaska’s Fund divides investment income among dividends to residents, funding for government services (like healthcare and education), and reinvestment. In other words, unlike Alberta, Alaska’s current approach preserves the Permanent Fund’s principal for future growth while still providing substantial annual support to both residents and government programs.

What Alberta lost

Given these comparisons, the Heritage Fund looks like a lost opportunity of massive proportions. While Norway sends 100% of its net oil revenues to its fund and Alaska sends 25% of resource royalties, Alberta’s governments have contributed next to nothing for decades. Even the current plan by Danielle Smith’s UCP government to increase the Heritage Fund to $250 billion by 2050 does not commit the province to annual contributions.

According to an estimate by University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe produced in 2020, the Heritage Fund could have been worth as much as $575 billion if Alberta managed it similarly to how Norway manages the GPFG. Now, let’s say Tombe’s calculations are off by a wide margin or, better yet, let’s reject Tombe’s assumption that Alberta could have saved at the same rate as Norway. Instead, let’s settle on a more conservative hypothetical estimate—that Alberta could have saved and invested well enough to have $150 billion in its fund, about a quarter of Tombe’s figure.

Based on a cautious ~3.3% annual draw (the Heritage Fund’s current 10-year annualized return is 7.6%) this would have nonetheless provided Albertans with around $5 billion in recurrent income. Meaning that if every one of the province’s residents were to receive an annual dividend of $800—twice the Ralph bucks—for a total of $4 billion, there would still remain $1 billion to spend on other initiatives, like new hospitals, schools and transportation infrastructure, each and every year.

Instead, Albertans are stuck with a fund worth a fraction, and continue to suffer with under resourced public services. In 2024, the Alberta Medical Association called on the province to declare a health care crisis due to growing surgery, emergency room and ambulance wait times. On the education front, the government’s own figures reveal that hundreds of schools are chronically overcrowded. And affordable social housing has remained scarce and underfunded. None of these problems should exist in a resource rich province exploiting oil for decades.

The way forward

It’s never too late to start saving. Alberta should reinstate regular, legislated contributions to the Heritage Fund — a fixed portion of non-renewable resource revenues, as was done in the Lougheed years. The $2 billion infusion pledged by the current government is a start, but contributions must be reliable and annual.

Alberta must also break its habit of using Heritage Fund investment income as a substitute for tax revenue to pay for general expenses. For the foreseeable future, the priority must be to allow the Fund to benefit from compound growth. To ensure this happens, the province needs to generate more revenue, whether through increasing personal income taxes, corporate tax hikes, raising resource royalties, or instituting a windfall tax on oil companies during boom times.

While some in Alberta have argued for a sales tax, a more compelling and politically astute first step would be to increase income taxes as well as corporate taxes. Though sales taxes are widely accepted outside Alberta, they are a regressive form of taxation, hitting those with lower incomes relatively harder. They can also become a serious liability for Alberta politicians, as Premier Jim Prentice found out in 2015.

In contrast, personal income tax increases could be targeted to high earners. And a general corporate tax increase would target big businesses—those with annual profits above $500,000, meaning the mom-and-pop shop down the street would not have to pay more.

Who would certainly have to pay more are the corporations that rake in hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in revenues, including the companies actively exploiting Alberta’s oil sands. In 2022, Canada’s five largest oil sands producers reported profits of over $35 billion. Let that sink in: in just one year, these oil sands producers made $10 billion more in profits than the total current value of the Heritage Fund. Put another way, these five companies made more money in one year than the total cost of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

To be sure, excessive profits continue to the present, with Imperial Oil reporting its best ever quarter in 2025.

Alberta’s conservative governments remain hostile to the idea of tax increases. Its politicians as well as those fanning the flames of western alienation seem to prefer pointing fingers at the federal government. But the facts speak for themselves.

Had the province spent the last four decades soundly managing its resource wealth and steered clear of the temptation to use resource revenues to keep taxes artificially low, Alberta could have been currently providing residents substantial annual cash transfers and adequately funding its public services, while also being far better financially prepared for a future where oil revenues are expected to decline.